How the workweek changed in the early 20th century

And what that means for knowledge workers today.

Our modern work week is relatively recent. It only became 8 hours a day, 5 days a week in the late 1930s. The progression to a 40 hour week is instructive because it represented a step change in both productivity for workers and for the types of work that were getting done. As we’ll see, this step change seems to emulate the step change happening among professional workers today.

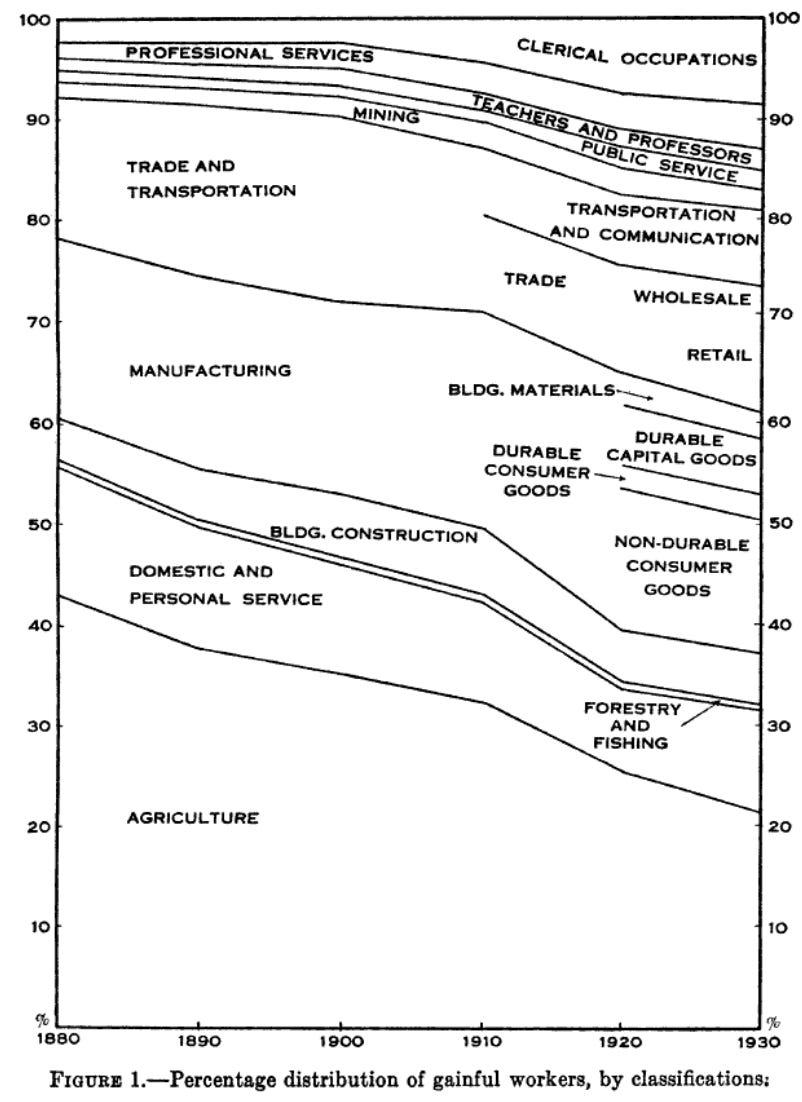

By the late 19th century, most work was starting to evolve from strictly agrarian day labor to factory work operating in shifts. Factories could produce goods fast, could pay a reliable wage, and were less subject to the whims of the consumer and the weather.

For folks on the margins, it made sense to “move to the city” and get a factory job rather than operating a small farm. Even productive small farms faced pressure from consolidated and larger farms, which were more efficient on a per-dollar basis and employed fewer people.

Other industries, like construction, took the advantages of improved tooling and technique and increased total productivity, without significantly changing workforce participation (as a percentage) because the demand for such services increased correspondingly.

Such increases in labor productivity did not necessarily mean that the people doing the labor needed to work less. On the contrary, the increase in productivity led to three somewhat independent phenomena:

The increase in productivity changed the nature of the work. Where previously, you had to hand tool the aluminum into the shape of the car, now you had to watch the aluminum stamp and make sure there wasn’t extra aluminum shavings in the edges.

The types of people entering the workplace were those who were previously unable to work - women being a notable example, but teenagers being the other.

Employees occasionally had leverage to start pushing for fewer work hours, often through trade unions.

Note the difference between workforce productivity and employee productivity. Employees could be way more productive, but it only translated somewhat to the company or industry as a whole, because some of it was lost in working hours changes and other inefficiencies. As Roos argues [1]:

In the case of the shoe industry, changes in man-hour productivity amounted to nearly 50 per cent, but, as indicated in Table II, employees’ productivity only increased about 25 per cent; that is, the employees were working less hours in that industry. In the rubber tire and tube industry, man-hour productivity was almost doubled, but employees’ productivity showed an increase of only about 40 per cent. A similar story can be told for the twenty industries whose statistics are available.

When we look at work week statistics, the average work week dropped by roughly 4 hours every decade between 1900 and 1940 as the economy grew rapidly. [2] The average does obscure what would typically happen in each industry, where work week adjustments would happen rapidly and then plateau for a while. Still, the overall trend is pretty easy to see.

Interestingly, the trends that allowed workers to negotiate shorter days also allowed them to negotiate part-time engagements in the 40s.

The rise in the number of part-time workers in nonagricultural industries is to a large extent the result of the rapid increase in the number of married women workers over 35. (See table.) Many of these women prefer part-time work, and the employers, faced with a tight labor market, have provided part-time jobs.

What this implies for modern workers

It’s clear that knowledge workers coming out of the pandemic have the capability to be significantly more productive than they were previously. A combination of salaried work and remote work (so that hours can adjust to the employee’s schedule around other obligations) allow for employees to get more done, and for what they get done to be higher quality as measured in performance reviews.

However, like improvements in tooling in the 30s and 40s, organizational productivity has not necessarily seen similar gains. Is the typical tech company shipping more product, selling more value to customers, etc? It’s unclear. If anything, the recent tech layoffs reveal a tendency to overhire and accept greater inefficiency within most venture-scale companies.

Like it has before, the tooling improvements have not outweighed overall economic growth - we do seem to see an increase in labor participation, though the increase is less demographic and more geographic in nature (a tech company in California can now hire in Louisiana for its employees).

What hasn’t happened as visibly is employees pushing to adjust their working hours to match the increased productivity. “4 day work weeks” is predominantly a cultural meme among a few tech companies (and a couple of countries) in pilot experiments, and unions are significantly underpowered relative to their counterparts a century ago.

However, the basic economic reality is not so different from what it was before. Ever increasingly productive employees have the leverage to negotiate adjustments with their companies, if they choose to use it.

[1] Roos, Charles F. “Economic Theory of the Shorter Work Week.” Econometrica, vol. 3, no. 1, 1935, pp. 21–39. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1907344.

[2] Zeisel, Joseph S. “The Workweek in American Industry 1850–1956.” Monthly Labor Review, vol. 81, no. 1, 1958, pp. 23–29. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41833823.