Showing face is more important than getting things done

Working remotely may give you increased productivity, but it might make you less likely to get that promotion.

It’s been interesting seeing the discourse around remote work coming out of the pandemic. Some companies think remote work is here to stay. They see the advantages of 1) being able to recruit outside of their geographic area 2) increased worker productivity and 3) reduced fixed costs (for things like offices) as key for continued company growth in 2023 and beyond.

Other firms see remote work as a disadvantage. They tend to think that worker productivity (and culture) is maximized when people are in-office, and that such productivity would outweigh the increased costs with continuing an in-person environment.

Workers seem to be less divided. Most seem to prefer having some flexibility, and therefore are pushing for hybrid or fully remote options for their companies. Knowledge workers tend to be providing some type of output that is not a function of how many hours they put in, so going into the office was always a “should do” rather than a “must do” in order to get the work done.

Now, as we exit the pandemic, fully remote workers are starting to look over at their now in-person colleagues. Will they get passed over for advancement opportunities and raises because they aren’t in the office?

Are remote workers actually more productive than in-person ones?

In 2013, a research team tried to take a look at answering this question. They used data from call center employees at CTrip, a Chinese travel agency. Employees who were willing to work from home were randomized, some asked to work from home and some continuing to work in the office. Here’s what they found [1]:

Home working led to a 13% performance increase, of which about 9% was from working more minutes per shift (fewer breaks and sick-days) and 4% from more calls per minute (attributed to a quieter working environment). Home workers also reported improved work satisfaction and experienced less turnover, but their promotion rate conditional on performance fell. Due to the success of the experiment, CTrip rolled-out the option to WFH to the whole firm and allowed the experimental employees to re-select between the home or office. Interestingly, over half of them switched...

13% is substantially more productive! It translates to one additional (free) employee for every 8 you hire. It’s not clear if it applies to every type of remote work or only “task-based” work like you’d find in a call-center, but it’s impressive to see a consistent improvement in productivity when workers choose to go remote.

Will working more productively while remote help me get promoted?

You would think that companies seeing improved productivity would reward their workers with additional compensation or promotions. But unfortunately, remote work seems to count against workers in the perceptions of employers, despite the potential productivity boost. [2]

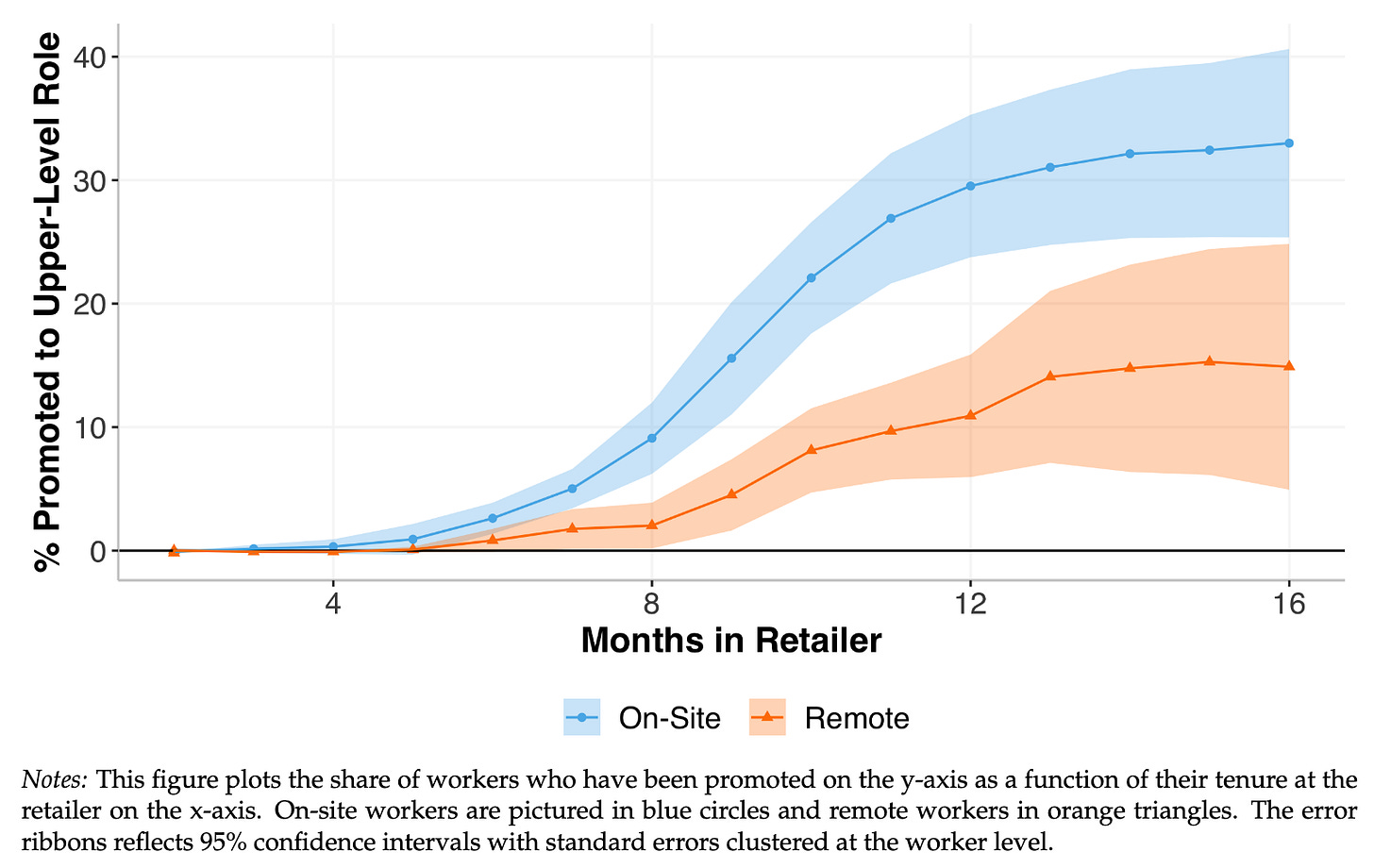

At our retailer, workers who chose remote jobs were 12 [percentage points] less likely to be promoted than those who chose on-site jobs, complementing the results of Bloom et al. (2015). We find suggestive evidence that these promotion differences reflect differences in the information that managers acquire about remote and on-site workers. Managers’ evaluations help predict the future performance of on-site workers but not remote workers. In our model, this motivates the hypothesis that working remotely increases the probability that capable workers will be overlooked for promotions.

My peers at other tech companies seem to be seeing the same phenomenon. Yes, you are likely to have been more productive working remotely than you would be in the office, but the perception is that your productivity is worse. And it’s that perception that dictates whether or not you’re getting a raise, so the best decision is for you to go back into the office, even if objectively it is worse for both the company and for yourself.

This sort of “inefficient market” for knowledge work labor should be disruptable, in the sense that remote firms should eventually out-compete those that incentivize showing face in-person. But at least within tech it’s not obvious that there are enough competitors in each market for in-person vs hybrid to actually be the differentiator for one firm vs another.

What type of person decides to be fully remote?

The researchers also note an interesting selection effect which is worth discussing. What happens if, rather than having both onsite workers and remote workers work remote and measure their productivity, you list remote as an option when you hire someone? Does that select for people who are less productive? Do people see remote as a way of slacking off on the job?

Unfortunately, it seems the answer might be yes:

the difference in these differences suggest that the offer of remote work attracted workers who were 18.8% less productive, despite receiving same pay and always being trained on-site. This design complements the analysis in Linos (2018), which finds similar patterns in the US Parent Office around its introduction of a work from home program.

Get that? So working remotely makes you 13% more productive, but posting a remote job gets your company candidates that self-select to be 18.8% less productive. Yikes. Net-net it actually may be better for companies not to support remote policies, because the people who choose to use them will work less than they should.

Yes, but what should I do?

It’s not clear what you should do about this research if you have a day job.

For example, if you’re currently going into the office, you’re likely to be 1) less productive but also 2) more likely to get promoted. Perhaps that means if you’re on your way up, say as a young employee, you should be going into the office more. However, if you’re at a relatively high position in the organization and are unlikely to move up further, it might be worth considering going remote. You’ll be more productive, assuming you didn’t select the job solely because you had the option of going remote. And your career was already stagnating.

If you’re a hiring manager, I think this pretty definitively suggests that you should regard purely remote candidates with some suspicion, and possibly having a higher hiring bar for those individuals you think are worth hiring remote. That would allow you to “correct” for the self-selection problem while also taking advantage of their intrinsically higher productivity.

[1] From Bloom et al. Working Paper. “Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment”. This paper has been cited dozens of times in news articles talking about pandemic working, so thought it was a good paper to start with on the inaugural newsletter post!

[2] From Emma Harrington and Natalia Emanuel. Working Paper. “'Working' Remotely? Selection, Treatment, and Market Provision of Remote Work (JMP)”. Note that their most recent version of the paper actually found remote work decreased productivity.

Our results suggest that remote work not only reduced the quantity but also the quality of calls for two out of the three quality metrics. Around the office closures of Covid-19, customer hold-times increased by 11 percent for formerly on-site workers going remote relative to already-remote workers (p-value = 0.028). An analogous difference-in-differences design indicates that remote work increased customer call-back rates by 3 percent, suggesting that workers were less likely to fully answer customers’ initial questions when at home (p-value = 0.045).

The productivity of remote workers is something we’ll revisit as research continues, since it seems to continue to be an open question. There is emerging evidence that it depends on what sort of work is being done, and how easy it is to measure.