The idea of 4 day work weeks is getting more popular by the year. What was previously a rare occurrence now has large government trials assessing its effectiveness. Still, there are some ways in which the research around 4 day work weeks leaves something to be desired.

4 day week vs 5 day week, keeping hours the same

Research around shortened work weeks exists back to the early 1900s, but the oldest relevant study (that is, research on non physical labor work) appears to be in 1973, in a study of workers at a pharmaceutical company. [1]

The company was looking to understand what would happen if workers went from 5 days of 8 hours each to 4 days of 10 hours each. By keeping number of work hours the same, the researchers provided a nice opportunity to measure effects that theoretically should not change, like productivity.

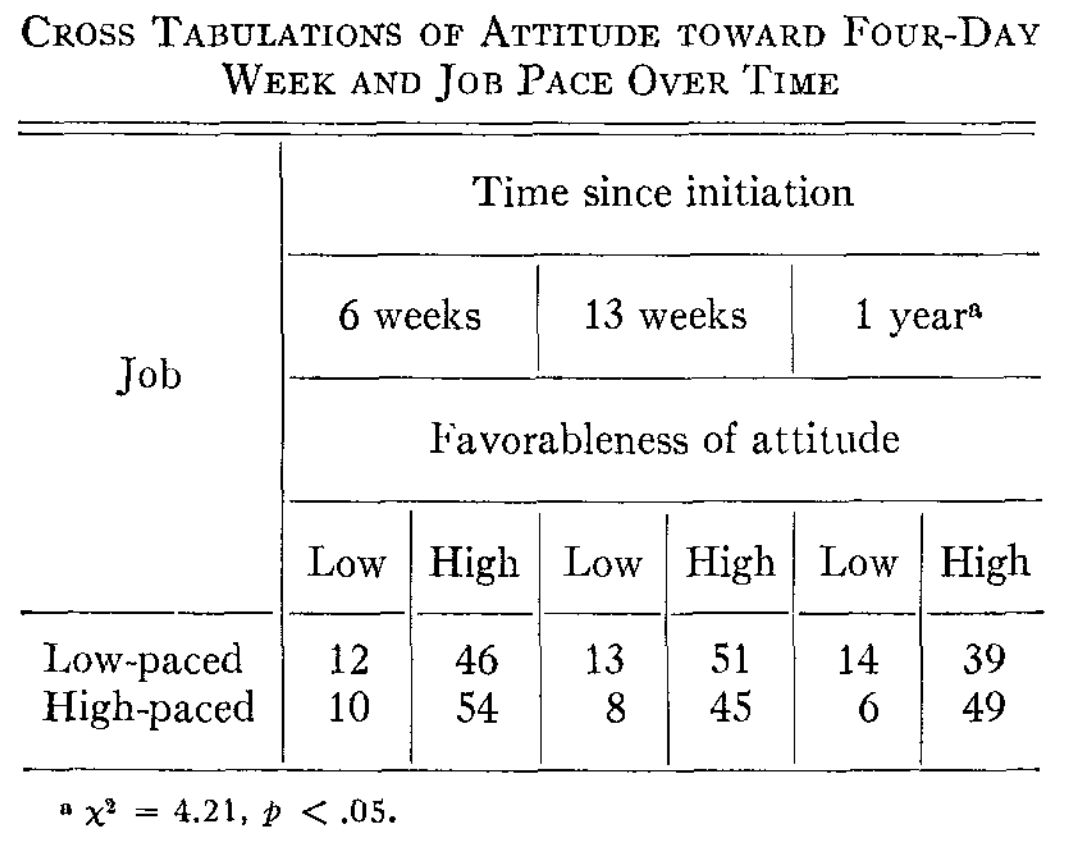

Measured qualitatively by workers, job pace and productivity were radically increased, even 1 year after the change to 4 day work weeks was made. This seemed to apply to all types of workers at the factory, though the effect seemed to be weakest among low skilled workers.

This study has been replicated many times. Moving from a “5-40” (5 days of 8 hours each) shift to a “4-40” (4 days of 10 hours each) seems to improve productivity and happiness on net, and therefore the adherence to 5-day a week culture for most office jobs seems to be one of tradition rather than one that optimizes for efficiency.

4 day week vs 5 day week, where hours are proportionally scaled down.

The question then is - how much do those extra 2 hours a day actually help? Is it possible that 4 days of 8 hours each actually produces as much output as 5 days?

Administrators in Iceland attempted to answer that question. Their hypothesis was that while Iceland’s overall productivity was high, it was low per hour worked, because Icelandic workers tended to work a lot. As part of their evidence for making an intervention, they demonstrated that (in general) per hour productivity goes up as working hours are reduced.

The trial was fairly straightforward:

Initially, two workplaces were selected. The first was a service-centre for Eastern parts of Reykjavík City, Árbær and Grafarholt, while the second was the Reykjavík Child Protection Service. Both were chosen on account of the high levels of stress present in each workplace, which shorter working hours aimed to reduce. An additional workplace was also selected as a control group for comparison. This was also an office location, albeit one that administered different duties. The trial commenced in March 2015 with these two workplaces shortening the hours of their workers, seeing 66 members of staff participate. Hours per week were shortened from 40 hours to 35 or 36, depending on the particular workplace. No change was made in the control group workplace (Reykjavík City, 2016)

The outcomes from the research were interesting. They showed that workers that moved to the 4 day work week:

Really did reduce working time (workers did not compensate for the shorter week by working more overtime)

Productivity as measured by specific output of the organization remained the same or increased. The easiest place to see this is measured by call volume / case closure rates, but other metrics also remained strong.

Saw significant improvements in wellbeing (spending more time with children, helping more with home tasks, exercised more, and had less stress at home).

No free lunch

The researchers did point out one significant downside to their research. While per hour productivity for 4 day workers went up, the absolute amount of productivity for certain jobs was not actually enough.

It should be noted that unlike the trials, not all these changes were brought about cost-free. Though in some cases reduced working time did not have a financial impact, due to the productivity gains achieved in the trials, there were a number of workplaces where this was impossible and more staff had to be hired. Increased costs for the Icelandic Government are estimated to be 4.2 billion ISK yearly (24.2 million GBP, 33.6 million USD) due to increased staffing in healthcare — indeed, two-thirds of the total costs are estimated to be in healthcare alone (Ingvarsdóttir 27 April, 2021). To put these numbers in perspective, however, the budget of the Icelandic Government in 2019 was 891.7 billion ISK (5.1 billion GBP, 7.1 billion USD; Government of Iceland, 2018, p. 3). Hence the overall cost remains a fraction of total state spending.

While the report attempts to paper over this difference, it’ll be important for future 4 day work week studies to explore this connection.

To the degree that absolute productivity can be measured, do employers have to increase headcount in order to compensate? How does the headcount trade-off against the increase in per-hour productivity?

Answers to these questions could take us down a few different paths. But one in particular we’re interested in exploring: determining whether it might be more profitable for firms to hire more workers and have each worker work fewer days at maximum productivity. We’ll explore the evidence in either direction in future posts.

[1] Nord, W. R., & Costigan, R. (1973). Worker adjustment to the four-day week: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 58(1), 60–66. doi:10.1037/h0035419

[2] Haraldsson, G. D. & Kellam, J. (2021). Going Public: Iceland's Journey to a Shorter Working Week.