Do hybrid employees work more than fully in-person ones?

One study suggests that hybrid workers work harder, take fewer days off, and are at least as productive as in-person workers.

Last week, we examined two studies that indicated remote vs onsite was a difficult choice. If you chose to be onsite, you’d be less productive but more likely to be promoted. If you chose to be remote, you’d be more productive, but the sort of people who elected to be remote tended to be the less productive cohort of employees. Unfortunately that meant that even though for you as an individual working remote might be better, the game theory for the employer might actually push them to force employees to come into the office. The employer has to deal with employees in the aggregate, and so will choose a global optimum even if it’s locally inefficient.

However, there were gaps in the studies we examined before:

Few workplaces are forcing a “fully remote” and “fully onsite” dichotomy among their workers. Most knowledge workplaces are presenting a third option called “hybrid”, usually expecting employees to come into the office 2-3 days a week, and allowing them to work remotely the rest of the time.

The studies we examined before were of call center workers. Call centers are an interesting job in that the work can be done from anywhere, but it’s different from traditional knowledge work in that performance can be directly measured “per hour” or “per task”. It’s unclear if changes in productivity for call center workers is indicative of changes in productivity for jobs like software engineer, product manager, UX designer, and so on. Moreover, the latter jobs tend to involve a lot of collaboration in a way that might change the productivity equation.

So, the ideal study to examine would be one that examined more classic knowledge work jobs rather than “solo productivity” ones, and allowed us to probe the difference between hybrid and onsite performance.

How do hybrid workers perform relative to onsite ones?

One Chinese software company decided to carefully measure this in 2021 [1]. Like most software companies, they primarily employ the types of digital workers that we’re most interested in: marketers, software engineers, professional managers, etc.

It’s important to recognize that the bias in China is towards onsite work as the “best” way to get productivity out of employees, and so is similar to some tech firms in fearing people will “slack off” when working from home. As the researchers noted:

The key obstacle to implementing hybrid WFH was the concern of many managers that employees would underperform on their days at home. In addition, in 2021, no major Chinese firm was offering hybrid WFH, with total attendance at the office the norm. So [the company] decided to formally evaluate a hybrid WFH system in two divisions over six months before making a decision over a full firm roll-out.

Senior management at the firm was surprised at the low volunteer rate of the optional hybrid-WFH scheme. They suspected that many employees were hesitating because of concerns that volunteering would be seen as a negative signal of ambition and productivity. So…all the remaining 1094 non-volunteer employees were told they were also included in the program.

The company took all those employees who had “odd birthdays” (they were born on the 1st, 3rd, 5th etc of the month) and asked them to work from home on Wednesdays and Fridays, while their counterpart “even birthdays” were asked to come into the office every day.

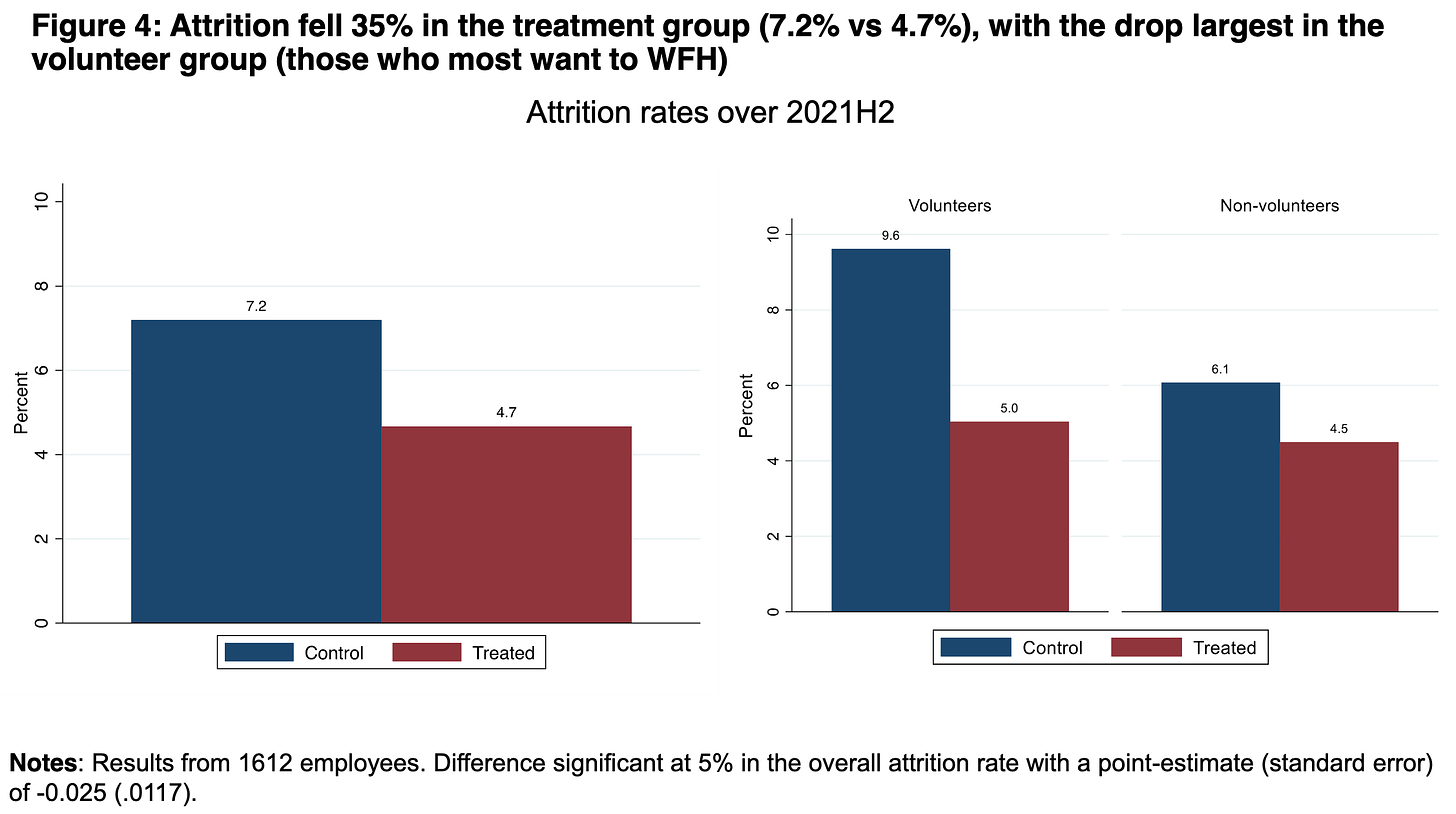

One interesting finding was around employee attrition [2]. Workers that were selected to WFH had much higher job satisfaction and so stayed in their roles longer.

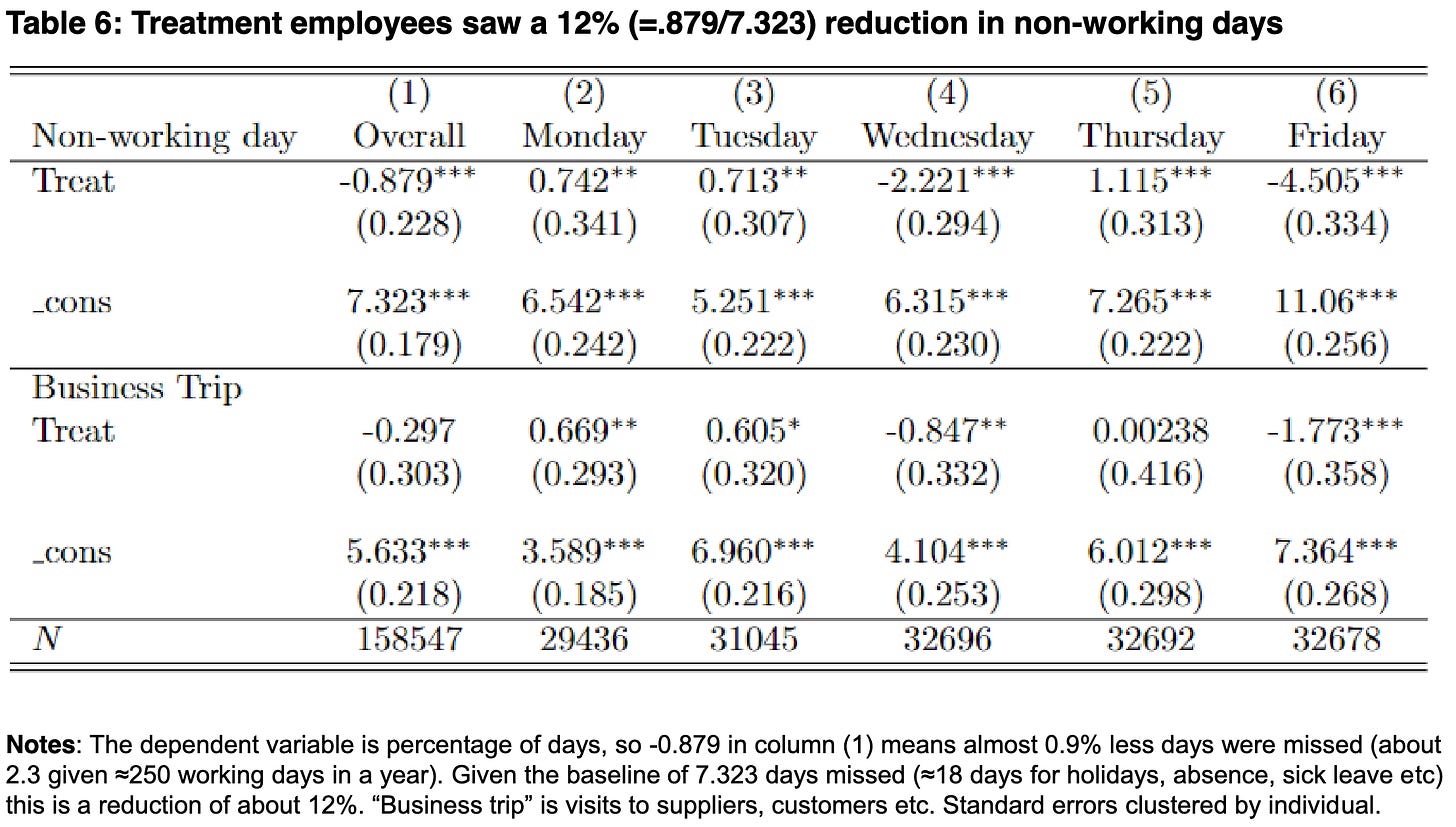

But more interesting was that employees who were hybrid seemed to work more. For example, they took fewer vacation days.

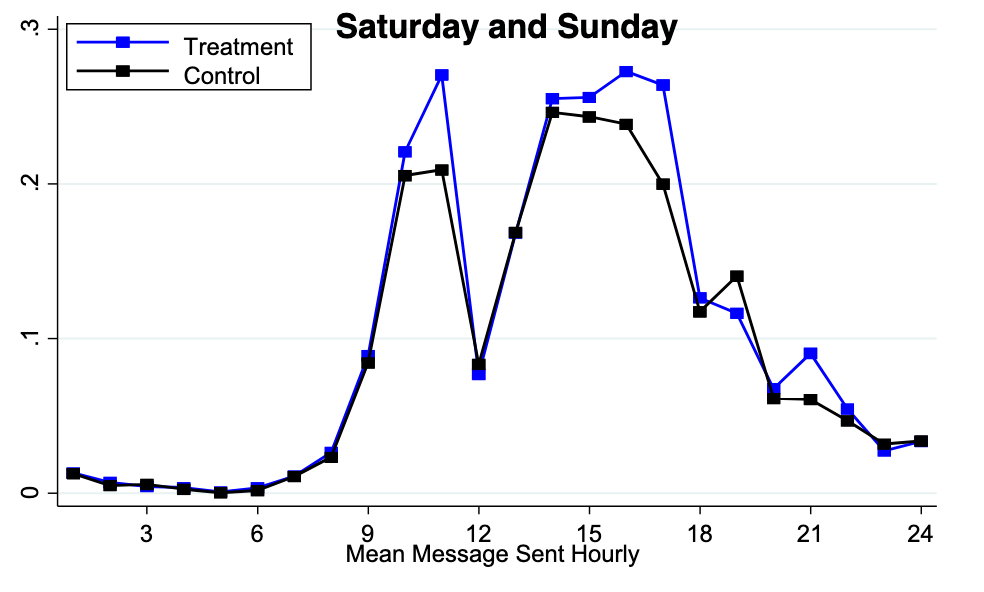

The researchers were even able to measure the amount of hours of work spent (by looking at VPN logins) and number of email / instant messages sent. Hybrid workers sent more messages on weekends than the regular onsite workers on average. And productivity in terms of “lines of code” was higher (as flawed as that measure is).

However, the researchers did find a slight net reduction in work hours. These actually seem to indicate a positive assessment of WFH - higher productivity with slightly fewer hours.

This shows some clear substitution of working time across days, in that employees work more than an hour less on WFH days but appear to (in part) make up for this on other days. Interestingly, although treatment employees appear to work about 0.8 hours less a week, given their similar performance and promotion results and increased coding output, they likely work more efficiently per hour. This would

be consistent with the results of higher WFH working intensity in the Bloom et al. (2014) paper, where employees working at home had a higher output per minute and took fewer breaks within their working day.

What does this imply about WFH policies and the push to return to office?

At least on first inspection, the push to return to office full-time seems to be a mistake from the employer’s perspective. This study shows a stronger productivity improvement by almost every measure except number of hours worked, with the implication that productivity per unit hour actually goes up and would probably be a good thing for both employer and employee.

Thinking more broadly, it’s unclear if the increased productivity of WFH is apparent to existing organizations. It appears to be the case that knowledge workers have the option to WFH part of the time, but only as an overhang coming out of the pandemic, and the fear of incentivizing attrition by pushing people into the office. (That fear appears legitimate, given the above attrition data).

Companies are often pushing return to office by providing a reverse incentive: applying salary cuts or adjustments if the employee chooses to work from home, even if they remain in a expensive market with many options for employment. That incentive appears to be a strategic mistake, but only if the quality of work happening from home is equal to that in the office. In subsequent posts, we’ll examine this question and see what the data seems to suggest.

[1] Bloom et al. “How Hybrid Working From Home Works Out”

[2] This implies that attrition may have been artificially low during the pandemic, and (fears of a recession aside) there may now be a catch up effect for workers who now have the opportunity to go back into the office.